The shipbuilding market in 2005

2004 SAW A SERIES OF HISTORICAL RECORDS BROKEN, 2005 WAS NO LESS REMARKABLE :

1 -The demand remained substantial, despite higher prices and a lack of early newbuilding slots. The world shipbuilding orderbook has, again, risen over the past 12 months, from 165 million gt to more than 175 million gt, just over 2,150 ships ordered against around 1,700 ships delivered over the same period. The orderbook is spread out over three to four years. South Korean and Chinese shipyards are already booked for some 2009 deliveries, while several Japanese yards' schedules go up to 2010. The rare slots available for 2007 or 2008 deliveries, which arise from new born yards or when existing builders optimised their schedules, were promptly sold to very willing buyers and constitute marginal quantities.

2 - South Korea has again strengthened its leading position with an orderbook rising to 65.6 million gt against 62 last year. Japan follows with nearly 54.2 million gt, a level which is identical to 2004. China has also reaffirmed its third position with 30.6 million gt against 27 million a year ago. Benefiting more than ever from the Asian builders 'sold out' status, Europe's shipyards' orderbooks have risen from 8.4 to 12.3 million gt for Western European yards and 7.5 to 8.7 million gt for their Eastern neighbours. The rest of the world (Vietnam, India, Russia, Brazil'), where earlier delivery dates can still be found at sometimes cheaper conditions, have remained attractive and their global orderbook has been maintained at nearly 7 million gt.

3 - Newbuilding prices registered their strongest progression during the first half of 2005, when the demand for containerships peaked, lifting the entire shipbuilding market to new highs. The other ship categories, such as MR Product tankers (47,000 dwt), also benefited from this force of attraction. Historical levels were reached. However, such price levels in conjunction with freight rates, which stopped making progress from the mid-year, have started to put some clouds in the owners', so far, bright clear sky. Some analysts are starting to say we have reached the crest of the wave, or would like to prove that the newbuilding market is heading towards very rough weather. More experienced and long term market observers feel there is no need to panic if freight rates have indeed reached a plateau in 2005, they have remained at healthy levels compared to those recorded in the past, and with three or four years of work in the orderbooks, builders are far from thinking about a readjustment of their prices, especially at a time when they are delivering ships ordered at the bottom of the market (in 2002 or during the first half of 2003) on which they are currently losing a lot of money. The years 2009/2010, which are predicted as potentially negative by some analysts, are still too far into the future and a lot of events can simply occur in the meantime that could completely change market fundamentals with negative, positive or, more likely, mixed results.

4 ' Shipbuilders, who had been struggling since 2003 with unprecedented cost increases in steel, engines, equipments, along with the depreciation of the dollar and rising wages, have finally in 2005 seen their operational result improve throughout the course of the year. The price of steel, on which builders have almost no influence considering that shipbuilding only counts for 1 % of the world steel consumption, has already started to decrease. Builders are also benefiting from higher downpayments of ships ordered at better conditions, but their situation remains unstable. The unexpected order boom has provoked a surge in demand for equipment, but there is no newcomer on this supply side, and these boosted prices created some bottlenecks and disruptions. The Chinese shipyards, who are starting to see what influence a floating currency can have on their business on 21st July 2005, are now living under the threat of a stronger revaluation of the RMB.

5 - The race towards gigantism has been pursued with the order of giant ore carriers of over 270,000 dwt. For the first time, the 10,000 teu barrier has been officially broken with the order of a series of 12 containerships by Cosco, six of them placed in South Korea at Hyundai H.I. and six in China at Nacks. These juggernauts will still use a single shaft propulsion associated with the most powerful diesel engines currently available. The next steps towards 12,000 to 15,000 teu containerships will most probably necessitate the use of a twin shaft system, as has been adopted for the giant LNG carriers of 266,000 cbm ordered in 2005 at South Korean shipyards. Some orders of large PCTC with a capacity over 7,000 vehicles have also been placed in South Korea and 5,000 passengers cruiseships are on the drawing boards. This trend toward gigantism is also reflected in some record breaking contracts, notably the letter of intent signed between Qatar and the three largest South Korean yards to build more than 90 LNG carriers in the coming years.

WORLD GROWTH AND INTERNATIONAL TRADE

The world economy, again, ran full speed ahead in 2005 with an overall growth of 4.3 %, though not beating last year's historical record. International trade has remained particularly healthy with a 7 % rise against 10 % in 2004.

The raw material markets have again been under pressure, reinforcing players' nervousness, which turned into a disorientating volatility of prices and freight rates.

FREIGHT RATES

FREIGHT RATES

Dry bulk freight rates were maintained at rather high levels during the first quarter of 2005. They only started to decline at spring time, as they did in 2004, but this time the fall was longer and deeper. Then, again like in 2004, rates went back up at the beginning of the summer. This upward trend was also slightly weaker and shorter, the rates falling again by the end of the summer. However, even if on average freight rates were lower than last year, they have remained quite healthy and still well above their 2003 levels.

In the containership sector, rates rose steadily during the first half of the year, on a trend which started in 2004. Historical records were broken and ships were taken for longer periods. The market then started to decline until the end of the year, only to return to levels similar to those recorded in 2004. Charterers were then more hesitant in taking on ships with deliveries three to four years out for long periods.

As far as the tanker market is concerned, earnings have been highly volatile, for instance the VLCC segment has registered peaks at over $ 100,000 per day at the start of 2005 and even $ 150,000 per day by the end of the year. Some severe setbacks were also seen particularly, in the early weeks of the summer, with rates hovering around $ 25,000 per day. But again, even if earnings were on average lower than during 2004, they are still pretty high and much higher than what they were in 2003.

ORDERS FOR STANDARD VESSELS

The world orderbook grasped a new record at 175 million gt this year, but the 100 million dwt barrier of new orders (which was broken twice, in 2003 and 2004) was not attained in 2005. However, it has been the third best year in the history of world shipbuilding so far, with a total of 95 million dwt of new ships ordered. In terms of number of ships over 3,000 gt (excl. offshore), 2005 ranks second with around 2,150 ships ordered against 2,450 in 2004 and 2,000 in 2003.

This rather moderate slow down observed this year is partly explained by the saturated production capacities (some builders having their schedules booked for 5 years!) but also by the level of newbuilding prices, and furthermore by the fact that some fleet segments are already highly rejuvenated.

Bulk carriers

Bulk carriers

With nearly 27.0 million dwt ordered, against 34.1 last year, the demand for bulk carriers seems to be easing. The orderbook, however, progressed to reach 70.5 million dwt at the end of 2005. The proportion of ships on order versus ships in service is just over 19 %, a bit lower than the 10-year record reached in 2004 with 22 %. In comparison to the tankers and the containerships, orders for bulkers were very moderate. Considering that deliveries of the ships currently on order are spread out over 4 years, this equals to a yearly growth of the fleet of less than 5 %.

This limited growth is, again, in a large proportion explained by the difficulties encountered by the owners to find newbuilding slots. The actual demand may have not in fact been completely satisfied.

South Korean builders have practically been absent from this sector for a long period of time now, deserting it in favour of ships generating higher income and added value. Daewoo should deliver the last 7 Capesizes they have on order in 2006 / 2007, and STX will deliver its last four Panamax (around 210 on order worldwide). The new Sungdong shipyard is the only one to be heavily involved in that segment, with 8 + 4 x 93,000 dwt and 5 x 26,000 bulkers in their orderbook. These are series of ships which have also ensured the new yard's launch and avoided direct competition with other products of the existing South Korean builders. No Handymax newbuildings are listed in the South Korean yards' orderbooks.

There is a relatively limited number of Chinese shipyards in competition for the main types of dry bulk carriers, apart from SWS, Bohai and Nacks for Capesize and VLOC tonnage, Jiangnan and Hudong for the Panamax, and Shanghai Chengxi, Dayang, Zhejiang and Kouan for Handymax bulkers.

Shipowners have nowhere else to go but to Japanese yards, whose market share in this ship category reached 65 % at the end of 2005. However, the latter favour their domestic clientele and some of them are full up to 2010 anyhow.

Owners must now consider possibilities offered in some other areas, like India or Vietnam.

If a little slow down was felt this year on the dry bulk side, the interest for Capesize tonnage has remained as strong as in 2004, with nearly 100 ships ordered and a fleet in service versus tonnage on order ratio reaching 28 %. Some owners and charterers even marked a renewed interest in the economies of scale on some routes and placed orders, for larger ships like very large ore carriers (VLOC), a fleet which is few in number and is ageing. Consequently, there are currently 24 x 270,000 dwt ore carriers on order for a fleet in service of 10 ships (excl. combination carriers).

Containerships

Containerships

With 23.6 million dwt ordered this year, the demand for containerships has been almost as strong as in 2004. In fact, 2005 was yet another record year as, in terms of the number of ships, no less than 573 ships (over 500 teu) were ordered, against 495 in 2003 and 549 in 2004.

This is also higher than the 535 tankers (over 3,000 dwt) and well over the 324 bulkers (over 4,000 dwt) ordered during the year 2005. If any proof is necessary, this is evidence that the whole shipbuilding market has been pulled by the demand in the containership sector.

The number of ships on order compared to the tonnage shows that the number of smaller sizes, (1,100, 1,800, 2,700, 3,500 or 4,300 teu), which are for most of them employed on feeder services, has increased this year, as shown in the following table.

The overall orderbook for containerships rose again to reach 61.4 million dwt, compared to 54.3 million dwt at the end of 2004. The tonnage on order amounted to more than 56 % of the fleet in service. Compared to tankers and bulk carriers, this has been one the fastest rising sectors

for nearly 15 years now, and it regularly triggers fear of overcapacity annually. In years to come, the fleet will increase by an average of 15 %, which is well over the expected rise of the world trade in volume. We can therefore expect a slowdown in this sector. We may have already reached the top of the hill during the course of 2005. Liner operators have started to be increasingly careful, refusing to commit themselves to long term charters and late deliveries, pushing rates down and indicating to the owners that the latter could not continue buying containerships at ever higher prices. The gap between the prices asked by the shipbuilders and the levels shipowners were willing to pay for new ships with distant delivery dates widened during the second half of the year.

South Korean shipbuilders kept a dominant market share in this sector, with 61 % of the world order'book at the end of the year. But the renewed interest for smaller units and the active search for the earliest newbuilding slot available, even with a premium on the price, have opened the way for some countries to increase their presence in this sector.

Tankers

Tankers

The demand for tankers has definitely drifted this year, with only 27.7 million dwt ordered, merely two thirds of the volumes ordered in 2004.

The orderbook remained globally stable, with 92 million dwt at the end of 2005. However the ratio regarding the fleet on order compared to the fleet in service, decreased to 26 % from 31 % last year.

The tanker fleet renewal process already started some years ago with the progressive introduction of double-hulls on new ships, which, at the same time, lowered the average age of the whole fleet, is now around 9 years for the larger sizes. Very few ships over 20 years are still in service. Besides, volumes of seaborne crude oil transported have remained fairly stable with only moderate increases.

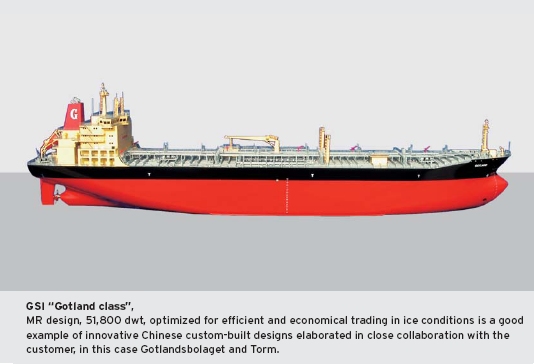

However, a clear distinction must be made between crude and pro'duct tankers, the latter having been under strong pressure, in particular as from the end of the summer 2005 following the series of hurricanes that halted a part of the US refinery capacity on the Gulf coast. Prices then remained stable and even increased slightly towards the end of the year. The market for product tankers is also favouring larger vessels and a significant number of coated Panamax tankers are now on order (around 120 coated tankers on a 134-ship orderbook), these ships being able to ensure triangular trade with either crude or oil products.

The maximum size of crude oil tankers ordered this year remained steady at around 2 or 2.1 million barrels (VLCC), no ULCC's have been ordered for several years now. The interest in ice-classed tankers is still there and, so far, 220 ships in the orderbook have an ice specification amongst the total of around 1,500 tankers of over 3,000 dwt on order.

ORDERS FOR SPECIALISED VESSELS

ORDERS FOR SPECIALISED VESSELS

The demand for specialized vessels remained strong this year. Apart from the gas carriers (LNG, LPG, ethylene carriers), owners found it very difficult to find shipyards willing to build ships considered technically complex.

Stainless steel chemical tankers

Stainless steel chemical tankers

The number of stainless steel chemical tankers ordered decreased from 78 in 2004 to 51 this year. The orderbook registered a small progression to 2.3 million dwt against 2.1 million at the end of 2004. The tonnage on order is only 17 % of the fleet in service against 16.5 % one year before.

Demand remained strong, but seemed to be of less interest to shipbuilders. Some major operators like Odfjell and Stolt decided to order coated chemical tankers, something they had not done for quite a long time. These coated chemical tankers are cheaper and will replace existing coated ships. This may be the first step towards a renewal process of the whole coated chemical tanker fleet, considering their cost efficiency, the level of price and availability of stainless steel, as well as simply the decreasing interest of shipyards to commit themselves to the construction of stainless steel tankers.

The largest operators in this sector must also struggle with growing competition from product tankers, which can carry easy chemical products, such as methanol, MTBE or vegoils, in bulk. Lastly, cargo tank coatings and additives to chemical products are becoming increasingly efficient, allowing a wide range of chemical products to be carried in satisfactory conditions.

LNG carriers

After a 400 % growth in the number of ships ordered between 2003 (20 ships) and 2004 (76 ships), only 49 newbuilding contracts were placed this year. The orderbook, however, stood at 140 ships (22.1 million cbm) against 113 ships (15.7 million cbm) at the end of last year.

This business is expanding quite fast and the carrying capacity on order now represents around 100 % of the fleet in service (23.1 million cbm for 193 ships). Some speculative orders had been placed since 1999, when the general rule was to order a ship with a long term contact attached, but the upswing in newbuilding prices has progressively restrained the appetite for such risky deals. The price of a 155,000 cbm LNG carrier went from an average level of $155 mil'lion at mid-2004, to $ 185 million at the end of last year, finishing the year 2005 at around $210 million.

The maximum size of LNG carriers, which remained around 125,000 to 130,000 cbm throughout the 1980s and the 1990s, probably due to technical choices made by Japanese yards, is now rising quite quickly. After making the first step between 140,000 and 165,000 cbm, the orders for two series of twenty Q-Flex ships of 210,000 to 217,000 cbm and six Q-Max ships of 263,000 to 266,000 cbm were placed by Qatar at South Korean yards. These ships will use the GTT membrane cargo containment technology and shall also be fitted with a two-shaft propulsion to ensure the lowest draft possible and to improve safety and manoeuvrability. They will also use a diesel engine and onboard re-liquefaction facilities. The monopoly of steam turbine propulsion is now over and the alternative of diesel, gas turbines and diesel-electric propulsion has appeared.

Japanese and South Korean yards dominate the LNG carriers newbuilding scene. In Europe, Aker has left the sector (but has considered a come back) and the fate of the Spanish conglomerate IZAR has still not been completely decided; the only yard which is remaining active is Chantiers de l'Atlantique. Elsewhere some newcomers are showing interest in this business, notably STX in Korea, plus Dalian, Nacks and Jiangnan in China.

LPG & Ethylene carriers

The number of LPG and ethylene carriers ordered this year is more than twice that of 2004, 120 new contracts having been signed in 2005 against 45 the year before and only 26 in 2003. Thus, the orderbook has increased quite strongly, going from 2.6 million cbm to 5.3 million cbm for a total of 183 ships. The orderbook stands at 36 % of the fleet in service against only 17 % twelve months before.

This market is booming driven by growing demand for growing volumes of LPG being brought into existence through the development of new LNG production. Forecasts concerning gas consumption in China and India, based on their equivalent in Japan or Korea, suggest that this market will keep on rising over the coming years. The freight rates, that had started to go up in 2003 and 2004, made further significant progress in 2005.

The renewal of the fleet, aged 17 years on average and including more than two thirds of ships aged over 20 years, is becoming an utmost necessity.

Some shipyards, particularly in Japan, may have arbitrated in favour of LPG carriers to the detriment of stainless steel chemical carriers, while some South Koreans, such as INP and STX, which originally specialised in product tankers, have diversified into these ships with a higher added value.

The bulk of the small LPG carriers orderbook was ordered in Japan, but some ships are also being built in South Korea, China and Italy. The VLGC (Very Large Gas Carriers) orderbook is mainly Korean, apart from some ships which are to be constructed at Mitsubishi or Kawasaki in Japan and also at Gdynia in Poland.

The maximum size of the ships currently on order is 82,000 cbm. If this industry continues to grow, some operators may decide to study the option of ordering larger VLGC.

Ferries and ro-pax

With 34 new orders this year, this is the second year in a row in which this sector has registered an increase in the demand for ferries and ro-pax vessels (27 in 2004). Consequently, the orderbook rose from 46 to 65 at the end of 2005.

The ageing fleet and the need for replacements have been the driving force behind the ordering of larger and faster ships. But this market is still suffering from the competition, in particular, of low'cost airlines and from the cancelling of tax free sales between EU countries. Consequently, the revenues of ferry companies are sometimes simply not sufficient to sustain the investment in new ships, and furthermore, only a few shipyards are really keen to work on such projects for which series of ships are the exception. Some operators, such as P&O, have even closed unprofitable ferry services.

This European market remains mainly in the hands of European builders, although some orders have gone to China. Buyers and traffic flows are also mainly located in Northern Europe or the Mediterranean area. Japan continues to have significant ferry and ro-pax traffic and this close knit domestic market's requirements are serviced almost exclusively by the Japanese shipbuilders. In China ferry traffic volumes continue to evolve in relation to the ongoing surge of economic development.

Ro-ro ships

Despite having been slightly more numerous than last year, the orders for ro-ro tonnage were very few, with only 14 new contracts signed, against 7 in 2004. The ageing fleet requires a certain level of renewal, but the ro-ro market is not expanding and is more subject to reorganisation of services than creation of new services, with an evolution towards faster and larger ro-ros, better suited to heavy trucks traffic.

In the longer term, it is possible that the development of short sea traffic may create new markets for such ships, but, despite the ever expanding road traffic, the 'high'ways of the seas' concept is hardly finding a favourable echo with trucking companies and efficient partnership schemes to associate government funding with private interests.

Car carriers

The number of car carriers ordered this year was halved, with 46 new ships against 80 in 2004. However, 2005 was the third best ever year in the history of the car-carriers fleet, and the orderbook keeps on progressing, having increased from a total of 137 ships (corresponding to a carrying capacity of 800,000 vehicles) at the end of 2004, to 150 ships (830,000 vehicles) at the end of 2005.

These new orders have been placed by the major operators and have been focusing on large PCTC (Pure Car Truck Carriers) with an intake of between 4,300 to over 7,000 cars. Reputed builders for such ships are very few, and are mainly located in Japan and South Korea, but also Croatia, Italy, Poland and now China, whose yards have this year successfully delivered their first car carrier newbuidings.

These ships are also being affected by the trend towards gigantism and the search for economies of scale.

This strong demand reflects the steady growth of the world car market. The relocation of production plants and the development of new markets, such as China, have boosted the demand for deep sea car shipments. The latest figures show the seaborne trade reaching 10.6 million vehicles by 2009, whilst 9.8 million cars were carried in 2005 (9.5 in 2004).

The need for an intermediate size of car carrying tonnage, around 2,000 and 3,000 vehicles, could emerge soon to ensure feeder services within Europe or Asia, to and from the large deepsea carriers ports of call.

Cruiseships

The year 2004 marked the rebound of ordering new cruiseships, with orders for 13 ships having been placed. 2005 was not far behind, as 11 large cruise vessels were contracted at European yards specialising in this very specific segment. The chapter dedicated to cruise vessels in this review details the orderbook and the most recent trends in this market.

Reefer vessels

With only 12 refrigerated ships on order (2.34 million cubic feet), the newbuilding activity in this sector remains almost null. The fleet is desperately shrinking and growing old. Only a handful of Japanese yards are still interested in such ton'nage and maintain a specific know'how (Kitanihon, Kyukuyo, Shikoku).

At the same time, the overall reefer capacity available on containerships has inexorably gained ground reaching 1,700 million cbft compared to 310 million cbft onboard purely reefer tonnage.

During the past two years, freight rates for reefer vessels have, however, recovered from a long period of low levels, improving profitability of the whole sector. The market still needs palletized ships to carry some seasonal products or to ensure direct services operated by some large reefer shipowners, for which containerships are not the best answer.

NEWBUILDING PRICES

Newbuilding prices in dollar terms took a fast and strong rise in the first half of 2005. Increases were up to 25 % for some ship types. This new take off in prices has undeniably been stimulated by the strong demand in containerships, but it has also been selfsustaining: owners, who could have decided to postpone their investments and wait for better times, have come to the conclusion over the last years that postponing their decision could eventually lead them to pay a higher price for their vessels, with a very remote delivery date. They also realized that waiting for better times could mean accrued delays in the necessary renewal process of their fleets as a result of orderbooks currently staggered over a 4'year time frame.

The newbuilding landscape started to change from the mid year when tanker, dry bulk and container freight rates dropped. Although still at high levels, freight rates found themselves mismatching newbuilding prices. Some analysts have been quite nervous about the size of the order'books and the increased shipbuilding capacity, which had them forecasting the newbuilding market to head towards rough weather. Due to the fact that psychology still plays an important role in the way the economy goes, this vision has had an impact on the behaviour of certain owners, who then thought waiting would be the best option.

The interaction between the newbuilding, resale and second-hand markets that snowballed newbuilding prices up very sharply, has progressively lost momentum.

The massive rise in prices that began in mid 2002 probably came to an end by mid 2005, when historical records in prices were broken.

Although the environment changed from mid 2005, newbuilding prices resisted the downward pressure and we are still far from the collapse that some had forecasted.

First of all, shipyards' management teams have remained calm. It is difficult for them to accept the principle of a decrease in prices, because of the simultaneous rise in their building costs. Despite a slight downturn in steel prices, energy (electricity, gas, fuel, petrol), which is an essential part of the industrial process, has become increasingly expensive, and so has ship's equipment. In fact, it is easier to create new shipyards whose main function is to assemble different parts than new equipment suppliers. Existing makers can currently hardly cope with the massive flow of orders and competition between them has diminished over time as a result of strong demand, remote delivery dates, uncertainties regarding costs and sometimes even components avaibility. The need for qualified workers in this fast growing industry generates payroll increases which are hard to estimate, especially for remote deliveries. Finally, in 2005 shipbuilders kept on delivering ships ordered at low prices, therefore showing mixed results once again.

The staggering of orderbooks over a very long period of time gives shipyards some latitude. Why should they decide to take active part in the decrease of newbuilding prices so as to receive more orders? Who could have forecasted the current boom 3 or 4 years ago?

From mid 2005, some owners started to hesitate, no longer accepting the prices offered to them by shipbuilders. The trend was starting to reverse itself. However, demand remained strong and shipyards were able to arbitrate between different types of ships. Those really eager for new orders consented to some discounts while owners willing to place new orders at all costs were bound to pay the price asked.

The spread between bid and offer eventually became wider for a few ship types: first for containerships, as the price of a 1,700 teu vessel went down from $ 37 to $ 32 million, but also for Handymax and Panamax dry bulkers whose prices decreased respectively from $ 32 to $ 30.5 and from $ 36 to $ 34 million.

The end of the rise in dollar based prices has coincided with the stabilisation, or appreciation, of the dollar against the local currencies of the main shipbuilders (won, yen, euro), with the exception of the Yuan, which the Chinese Authorities allowed to float as of July the 21st, 2005 (but with a smaller floating range than the other currencies). These fundamentals helped shipyards as a general rule. At early January 2005, one dollar was worth 1,044 won, 102 yen, 0,76 euro against 1,030 won, 120 yen, 0,84 euro by the end of the year.

Generally speaking, 2005's market remained a seller's market where shipbuilders were able to select their customers and their products, and did better than simply having a defensive strategy regarding their selling prices.

South Korea

South Korea

2005 was another record year for Korean shipbuilding, reaffirming its world leadership. The Korean orderbook included 62 million gt and 65.6 million gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It stood at 27 million gt and 42 million gt at the end of 2002 and 2003 respectively.

Korean shipyards are booked until the first or second quarter of 2009. Some berths were sold for delivery at the end of 2009 or early 2010, particularly for the construction of LNG tankers.

New orders represented 24.5 million gt in 2005 against 26.7 million gt in 2004, which is subdivided into containerships (9.1 million gt), LNG tankers (4.7 million gt), LPG carriers (1.6 million gt), oil tankers (7.4 million gt), bulk carriers (0.5 million gt) and others (1.2 million gt).

The Korean maritime industry is characterised by a tremendous vitality, great professionalism, a lot of rigour, an exceptional organisation and well qualified workers and staff. It is a concentrated industry. The competition between shipbuilders, with their numerous and demanding foreign clients, pushed them to great progress, reaching an exceptional level of quality. More than anywhere else, in particular Japan or China who have significant demand from their domestic shipping companies, Korea relies on its foreign clients.

The considerable increase in production at Korean shipyards forces them to find imaginative responses to enhance their development. Most of the large shipyards, created during the 70's and 80's, already expanded themselves during the 90's. Today, often enclosed by mountains and the sea, by built-up areas and the ocean, they need to find other places and human resources, while at the same time staying competitive. Investment and expansion plans are multiplying. To meet with demand, the builders are embarking more and more on dry-land construction (HHI, STX, Sungdong).

Hyundai Heavy Industries (HHI), the biggest shipbuilder in the world, already owns two building sites with HHI-Ulsan, HHI-Samho and has strong links with its neighbour Hyundai-Mipo, which controls Hyundai-Vinashin (HVS) in Vietnam, dedicated to repair and conversion work. HHI has commissioned a block constructing unit at Pohang (Korea). The HHI shipyards are also the biggest steel consumers, with 1.4 million tons every year. They suffered great price increases from their primary resource and therefore decided to invest in a steel mill in Korea.

Daewoo Shipbuilding, Machinery and Engineering (DSME) opted for a block constructing unit in Yantai (China), following the example of another Korean shipbuilder, Samsung, who has a similar sized plant at Ningbo. The production is due to start in 2007 with approximately 50,000 tons, to increase quickly to about 300,000 tons. Since 1996, DSME has also owned a Romanian shipyard (DMHI) and it is interested in a Philippine acquisition, which could be dedicated to ship repair and newbuilding.

Samsung Heavy Industries (SHI) received a new, 350 m long by 63 m wide, floating dock in 2005, which was constructed in China. This brings the number of floating docks to two, to which three graving docks must also be added.

Hanjin Heavy Industries (Hanjin), which specialises in containerships, is the only large Korean shipbuilder that does not own VLCC docks. It has been planning to expand itself outside the city of Busan for a long time, to meet with the demand for large containerships (8,000 teu and over), as well as LNG carriers. In late 2005, Hanjin decided to open a new shipyard in the Philippines, with a dock measuring 450 m by 100 m.

Large Korean shipyards are now dedicated to the construction of high value added ships, suitable for serial construction: very large containerships, LNG tankers and oil tankers (VLCC, Suezmax and Aframax). They retain, however, some specialties, like PCTC's and LPG carriers at HHI and DSME, or ice breaking tankers at SHI, without forgetting the offshore construction at HHI and DSME.

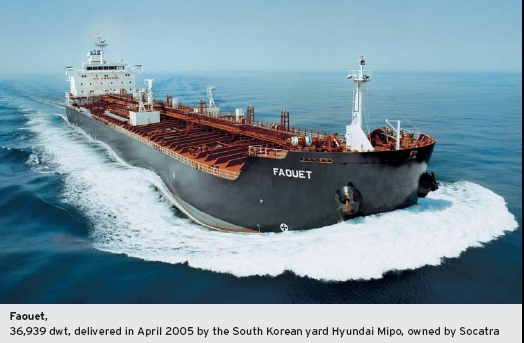

Hyundai Mipo definitely turned the page on ship repair at Ulsan this year, and the four available graving docks (VLCC-sized) are now fully dedicated to shipbuilding. The shipyard which delivered its first three newbuildings in 2000 built 45 vessels in 2005. In 2006, some 55 ships will be delivered and over 60 ships during 2007. HMD remains specialised in the construction of oil tankers and chemical tankers of 37,000, 47,000 and 51,000 dwt, as well as containerships of 1,800, 2,500 and 4,250 teu. But it is capable of seizing opportunities in other segments, and in 2005 it secured an order for 5 product tankers of 13,000 dwt for delivery in 2006 and 2007 further increasing its productivity and its turnover.

STX owns a graving dock and also constructs on shore. It has plans for the construction of a second dock (VLCC-sized) and intends to launch itself into the construction of LNG tankers. The core of its production consists of product and chemical tankers of 37,000 to 51,000 dwt, but also Panamax, as well as containerships of 1,800 to 4,250 teu. STX has also built LPG carriers and finishes a series of Panamax bulk carriers, contracted in 2002. After taking orders for 14 product tankers of 10,000 dwt for Clipper, STX Busan began the production of 9,000 cbm ethylene carriers.

Shina is specialised in the building of product and chemical tankers of 40,000 to 51,000 dwt. It owns two slipways and delivered 11 ships throughout 2005. Shina also contracted a series a four coated parcel chemical tankers with Stolt-Nielsen Transportation Group.

Small Korean shipyards were not lacking ambition and succeeded in remarkably breaking into the international market. INP had attracted some big names and counts for 20 ships on order. Others, like 21st Century, Samho and Nokbong, succeeded in selling long series of product tankers of 5,500, 12,800 and 13,000 dwt to different shipowners. Daesun continued its operations with the construction of containerships from 900 to 1,100 teu.

But in Korea there are also new shipbuilders, like Sungdong and SPP (ex-Dongyang) 'block builders that converted their sites into shipyards', shipyards that would like to expand, like Daehan, or simply brand new shipyards, such as Korea Shipyard. It is not always easy for these new entrants to obtain the bank refund guarantees necessary to execute building contracts, but they can offer their clients much earlier delivery dates and sometimes better financial conditions.

Japan

2005 was also a new record year for Japan, which maintained its second place in the world shipbuilding ranking. The Japanese orderbook continued to increase, and is now spread out over many shipyards until 2010: the production capacity is well saturated. The portfolio was maintained at about 54.3 million gt, having been 24 and 43 million gt in 2002 and 2003 respectively.

In 2005, the new orders represented 18.3 million gt, against 26.7 in 2004, which is broken down into containerships (1.6 million gt), tankers (4.6 million gt), bulk carriers (9.2 million gt), car-carriers (1.6 milion gt), LNG carriers (0.7 million gt) and specialised vessels (0.6 million gt).

In line with their Korean counterparts, Japanese shipyards are often enclosed between the sea and the mountains and, since their creation after the Second World War and the expansion of the 60's, have been caught by the urbanisation and industrialisation. But, apart from Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI) and Tsuneishi Heavy Industries (THI), which have invested in foreign countries (China and the Philippines respectively), it looks like Japanese builders have not been willing to follow the expansion moves of their Chinese or Korean neighbours. Of course, they have continued investing and rationalising their production facilities, which allows them to increase the number of ships delivered every year.

However, their strategies seem to be different. It is true that Japanese shipyards have a different history and that they, in particular, have overcome many shipbuilding crises, which certainly make them more cautious. They could, if they wanted to, reactivate some big 'mothballed' docks to satisfy, amongst others, the demand for large vessels (containerships and LNG carriers).

More than ever, Japanese shipyards give priority to very active, domestic ship owners. Next to the big traditional owners, like Mitsui OSK, NYK and K-Line, more and more local owners succeeded, in time, in constituting remarkable fleets, and their ships easily secure long-term employment with traditional owners, but also with Japanese trading houses and foreign charterers. Japanese owners accept more naturally to sign contracts in yen, which, for the shipyards, avoids exchange rates exposure. It becomes more and more difficult for foreign owners to order in Japan, which certainly is a pity, taking into account the excellent quality of Japanese shipbuilding.

Japanese shipbuilding continues to show much dynamism. Investments in technology enable the construction of standard vessels within very short building periods of not more than a few weeks in dry dock. The Japanese workers also made important efforts and sacrifices to cope with competition. Important differences in labour costs persist between big cities (Tokyo and Osaka) and the provinces. Will we see, as is the case in China, the closure of sites in urban zones and a redeployment of activities in less urbanised areas, in Japan or abroad? It remains an open question.

China

2005 was also a new record year for China, which continues to pursue its ascension, maintaining its third place in the world ranking. The orderbook consisted of 26 and 30.6 million gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It was, as a reminder, 9 and 17 million gt at the end of 2002 and 2003 respectively. It is a remarkable performance, when compared to the Japanese and Korean orderbooks, which stood at 24 and 27 million gt at the end of 2002 respectively.

New orders represented 13.5 million gt in 2005 and 12.6 million gt in 2004. Taking into account the current developments (expansion and creation of new sites), at the end of 2005 it was still possible to find delivery slots in 2008, but the majority of shipyards, however, are booked until 2009. The 2005 orders break down into containerships (3.5 million gt), tankers (3.95 million gt), bulk carriers (4.5 million gt) and specialised ships (1.5 million gt).

Expansion projects and the creation of new shipyards continue. Investments are immense and reflect the Chinese ambition: 1.4 bn yuan (e140 million), as an example, for the new site of Jiangnan on Changxing Island, where there will be four new docks of 380 to 590 m long and 80 to 120 m wide, enabling parallel and simultaneous construction.

China will be endowed with gigantic shipyards, capable of rivaling the biggest shipyards in Japan and Korea in the future. Chinese shipyards are already in competition with Japanese and Korean builders for most types of ships. VLCC are constructed at Bohai, Dalian, Nacks and Jiangnan (Changxing), VLOC at Nacks, LNG carriers at Hudong-Zhonghua (Dalian, Nacks and Jiangnan are also preparing to enter the LNG sector) and very large containerships of 10,000 teu at Nacks.

But, next to the big state or provincial projects, numerous private yards are flourishing in the coastal provinces of Zhejiang, Jiangsu, Fujian, Shangdong and Anhui and also on the banks of the Yangtze River and others, in the wake of the newbuilding boom. Meanwhile, the central government has restricted credit accessibility, and certain projects did not receive the necessary administrative authorisation.

Industrial restructuring continues. Chinese authorities are aware of the threats of overcapacity and the fact that the shipbuilders need to have a sufficient critical mass, together with a well established commercial strategy in order to improve their quality and productivity. CSIC notably succeeded in bringing together Dalian (Old) and Dalian New Shipbuilding, combining the production capacity of both under DSIC (Dalian Shipbuilding Industry Corp).

Following the example of Japanese shipyards, Chinese yards prioritise domestic ship owners, whose needs are very important and who could compensate for any slow down in international demand.

The weakness of the yuan continues to provide an indisputable competitive advantage to the Chinese shipbuilders, even if they have to buy various equipment from Europe, Korea or Japan. But after July 21st, 2005, the parity with the dollar changed and it is probable that new adjustments will be needed in 2006, by means of an increase in value of the Chinese currency.

Taiwan

2005 was also a new record year for Taiwan, which occupied the sixth place in the world shipbuilding ranking. The Taiwanese orderbook contained 2.2 and 2.4 million gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It was, as a reminder, 1.9 million gt in 2003. New orders represented 0.84 million gt in 2005, against 1.01 million gt in 2004.

Taiwanese shipbuilding is concentrated in the shipyards of CSBC and the orderbook consists almost only of containerships between 1,700 and 1,800 teu at Keelung, and between 4,000 and 8,200 teu at Kaohsiung, as well as a few Capesizes. Shipping companies like Yang Ming, Wan Hai and China Steel Corporation are the principal clients. But one also should count on a few foreign clients (Marubeni, Cido and Peter D'hle). Their orderbook extends until fall 2009.

Like many other mature Asian shipbuilders, CSBC is also looking to add capacity in lower cost areas and has been reported to be looking at various sites in China and elsewhere. CSBC is currently a state owned enterprise but is scheduled to be privatised.

Vietnam

The current healthy state of the market and the search for newbuilding berths has pushed ship owners towards new destinations. Vietnam is promoting its shipbuilding industry through the state owned group, Vinashin.

The Vietnamese orderbook consolidated and consisted of 510,000 and 670,000 gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. As a reminder, it stood at 150,000 gt at the end of 2003. New orders represented 240,000 gt in 2005 against 602,000 gt in 2004. Their orderbook extends until 2009.

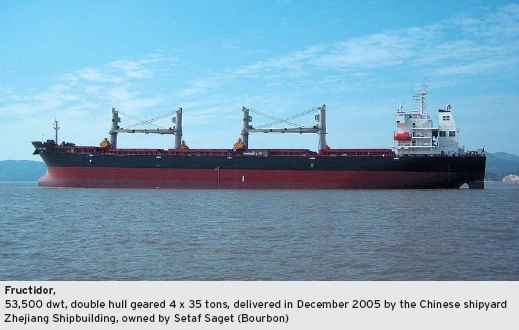

The Vinashin group today consists of a dozen shipyards, of which the principal ones are located in the North of the country at Haiphong (Ha Long, Nam Trieu, Pha Rung, Bach Dang'). In 2004 and 2005, the Cardiff (UK) based shipowner, Graig, placed orders for 27 Handymax bulkers (including options) of 53,000 dwt and 34,000 dwt Handysizes respectively. Ha Long, however, owns two new slipways, one measuring 250 m in length and 88 m wide, and another measuring 320 m by 36 m. Nam Trieu also has two, one of 180 m by 32 m and another of 320 m by 48 m. In principal, these yards could construct vessels of up to 100,000 dwt.

Vinashin also has development projects in the south of the country, at Saigon for example, and is planning new shipyards, capable of constructing ships up to 50,000 dwt.

Singapore

Besides repairing and converting ships, there still exists a strong tradition of newbuilding at Singapore, mainly focussed on offshore, which represented 90 % of the orderbook at the end of 2005, namely 110 units of all types: PSV, AHTS and tugs. But one can also count 20 merchant ships, including a series of six 2,856 teu containerships at Jurong.

Outside of the traditional presence in the field of naval shipbuilding, Singapore Technologies decided to position themselves in the ro-ro ship market. Other shipyards, like Labroy, have invested in new production capacity on the neighbouring island of Batam, in Indonesia, for the construction of supply vessels, cement carriers, plat'forms and barges.

India

Following Vietnam, India has also benefited from the scarcity of available newbuilding berths. The Indian orderbook consisted of 600,000 and 820,000 gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It stood at around 100,000 gt at the end of 2003. However, new orders represented 240,000 gt in 2005, against 570,000 in 2004.

It consists mainly of offshore supply vessels, small multipurpose vessels of 4,000 to 5,000 dwt, of which some have ro-ro capacity, and Handysize and Handymax bulkcarriers of up to 54,000 dwt. Shipbuilder Cochin will deliver the first of a serie of 6 bulkers for Danish ship owner Clipper, in 2006.

Iran

Iranian shipyards took some important orders during 2004 for domestic accounts and recorded four 24,000 dwt multipurpose vessels from a German owner in 2005, realising their search for international orders.

EUROPE

The West European orderbook has evolved in a substantial way, from 8.4 million gt at the end of 2004 to

12.3 million gt at the end of 2005. It stood at 5.9 million gt at the end of 2003. It has more than doubled in two years time. The East European shipyards equally proved their dynamism and saw their orderbook rise from 7.5 million gt in 2004 to 8.7 million gt at the end of 2005. Their orderbook stood at 5 million gt in 2003.

Over the past three years, the surge in prices has provided opportunities for European shipyards, although there, building costs are greater than they are in Asia. They succeeded in reconquering a clientele, which proceeded on the basis of a narrower gap in prices with Asian builders. They could also offer earlier delivery dates than those available from Asian yards, thus, justifying the much higher prices. The termination of provisional aid to European shipbuilders on 31st March 2005, even though it remained modest compared to the fluctuation of exchange rates, tempted certain ship owners to place additional orders. The weakening of the euro versus the dollar during the year gave a helping hand.

The expertise and the flexibility offered by European shipbuilders to ship owners, who wished to meet as close as possible with demand in their local traffic, are well appreciated, while at the same Asian shipyards, who pursue mass production, do not plan any other products than their standard designs.

Orderbooks at numerous European yards are filled up until the end of 2008, and for some, well into 2009.

The European shipbuilding industry should profit from such an improvement in order to increase its competitiveness and invest in production facilities. Contrary to Asian shipyards, many European shipbuilders lack the latest technologies which would enable them to considerably decrease the number of hours required to build a vessel, offer earlier delivery dates and improve the quality of the final product. In the past twenty years, Asian shipyards have realised a considerable industrialisation in the production. The outsourcing of hulls to East European yards should be considered as a short-term solution. The utilisation of cheap labour, whose cost can only but increase, should by no means compensate for the absence of technological investment. In 2005, it was possible for a modern Chinese shipyard to deliver a bulk carrier of 55,000 dwt 57 days after the steel cutting, with assembly in the dock taking not more than 18 days.

Chantiers de l'Atlantique, owned by the Alstom group, are to join the Aker Yards group, which already owns 13 shipyards in 5 countries (5 in Norway, 3 in Finland, 2 in Germany, 2 in Romania and 1 in Brazil). They will be part of a dynamic group, completely dedicated to shipbuilding (containers, cruise ships, ferries, tankers and offshore vessels) and will also benefit from synergies. The Aker development is good news, as it should ensure the everlastingness of Chantiers de l'Atlantique. With Aker, Europe also is endowed with a champion, capable of rivaling the Asian giants and of facing a clientele which has been consolidated for many years.

France

The French orderbook consisted of 450,000 gt at the end of 2004 and of 685,000 gt at the end pf 2005, mainly contributed to by the order of Mediterranean Shippping Company for two giant cruise ships of 8 130,000 gt and 3,500 passengers. As a reminder, the orderbook stood 6 at 380,000 at the end of 2003.

In 2006, Chantiers de l'Atlantique 4 will deliver 3 LNG carriers ordered by Gaz de France, whose deliveries were delayed due to insulation problems related to their containment system. The acquisition of Chantiers de l'Atlantique by Aker Yards will allow the latter to construct giant cruise vessels, whose studies are now under way.

In 2005, Piriou shipyard delivered 11 fishing vessels measuring 18 to 45 m, one refrigerated vessel of 83.2 m and two rapid intervention offshore ships. Its orderbook comprises of two trawlers, two tuna fishers and one aluminium passenger launch.

Constructions M'caniques de Normandie have delivered a 42.6 m long yacht in 2005 and have one corvette under construction for the Emirates navy, in a 6-vessel programme for the same client, as well as two yachts of 58 m and 42.6 m in length respectively.

Germany

The orderbook of German shipyards consisted of 3.1 million gt and

4.6 million gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It stood at

1.25 million gt at the end of 2003. In 2005, Germany was at the top shipbuilding spot in Europe and fourth in the world ranking, after China. New orders represented 2.8 million gt, of which 2.2 million gt was for containerships alone.

German shipbuilders took advantage of the strong demand for containerships during the first half of the year, and particularly of the current demand for feeder ships with a capacity between 800 and 3,700 teu.

They offered early delivery dates to domestic ship owners and German investors (KG), compared to Asian shipyards. Over 120 container carriers were ordered in 2005, against only 60 in 2004. In particular, Aker MTW currently has a very important order for a series of almost 50 containerships of 2,500 teu under construction. Germany continues also to be an important builder of quality luxury cruise vessels.

Italy

The orderbook of Italian shipbuilders consisted of 1.8 and 2.4 million gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It stood at 1.25 million gt in 2003. Italy occupies third place in Europe and seventh in the world ranking.

The 2005 orders consisted of some 40 ships for a total amount of 1.1 million gt, of which the majority were large cruise vessels, ro-paxes and large ro-ros. Italian shipyards booked more than half of their new orders for ro-ros, ro-paxes and ferries.

Fincantieri signed the biggest contract ever, for two cruise ships for the Carnival group, with a value of 2 billion euro. It also took 5 of the 11 cruise ships ordered during 2005 and has consolidated its place as a world leader in cruise ship construction.

Denmark

At the end of 2005, Odense Lindo, the only large Danish shipyard, had 16 containerships of over 9,000 teu (as usual, there is some speculation on the exact size of these container carriers) and two tugs in its portfolio, on account of its main shareholder, the AP M'ller group. The Danish orderbook accounted for 1.6 million gt at the end of 2005, which places it in the 4th rank in Europe.

Finland

This year, the three Finnish shipbuilding sites, all members of the Aker group, took in orders for 430,000 gt, including one 158,000 gt cruise ship '3,600 passengers for cruise company RCCL. It is the third in the 'Freedom'-class, which is to be constructed at the Turku site. The sites of Helsinki and Rauma are currently engaged in ferry and ro-pax orders.

Cruise ships, ferries and ro-ros constitute the majority of the Finnish production. The recovery of these sectors has been profitable to Finnish shipbuilders and their orderbook consisted of 550,000 gt and 880,000 gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It stood at 450,000 gt at the end of 2003.

The Netherlands

Dutch shipyards have taken advantage of the shipping boom and their orderbook consisted of 490,000 gt and 950,000 gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. It stood at 280,000 gt at the end of 2003. The portfolio constitutes about 130 vessels, of which the largest is a 15,000 dwt multi purpose freighter.

Dutch yards are continuing to outsource steel hulls to Romania, Ukraine, Poland and Turkey, with the notable exception of Ferus Smit, specialised in the production of small cargo ships and product tankers, whose production remained strictly local.

Spain

During the course of 2005, the Spanish orderbook came back to the same level as that of 2003, with a total of 450,000 gt. It fell to 135,000 gt at the end of 2004.

Small Spanish shipyards that accumulated most of the new orders in 2005, with notably a series of 20 multipurpose ships of 4,000 to 5,000 dwt ordered in series at Freire, Murueta and Marin shipyards. The biggest ships on order at Spanish yards are four ro-ros, of which the first two are 1,800 lane metres in length and the next two are 2, 100 lane metres, ordered in 2005 at Huelva, by the Clipper group, as well as stainless steel chemical tankers of 22,000 dwt ordered by Ultragas at Vulcano.

The offshore sector has also benefited the Spanish shipbuilders with orders of several PSV and safety standby ships during 2005.

The fate of IZAR was sealed in 2005: it will be dismembered. A governmental structure -Navantia' will take the old sites of Bazan, as well as the Puerto Real site. Production will be focussed on navy ships. The shipyards of Sestao, Gijon and Seville are subject to bidding and should be allocated to private interests in 2006. Since 2003, and awaiting privatisation, the Spanish government has not authorised these construction sites to take on any new orders.

Portugal

The orderbook of Viana do Castelo, the only large Portuguese shipbuilder, consisted of 7 cargo ships of about 8,000 dwt apart from an important series of ships for the national navy.

Norway

At the end of 2005, the Norwegian orderbook stood at about 300,000gt, comprising mainly offshore units, with the exception of two stainless steel chemical tankers of 45,000 dwt for Stolt-Nielsen at Kleven Flor'.

Poland

The Polish shipbuilders' orderbook is one of the few that lost ground last year, going down from 2.9 to 2.6 million gt between the end of 2004 and the end of 2005. However, Poland's position still ranks second in Europe and fifth worldwide.

This evolution may be explained by the situation of the main Polish shipyard, Stocznia Gdynia, which has now been working on a financial restructuring plan for more than two years. These difficulties, along with an important number of pending contracts for car carriers with one of its biggest shareholders, have prevented the shipyard from taking new orders in 2005.

In this context, the Stocznia Gdynia Group has committed itself to part with one of its affiliates, the Gdansk shipyard, the sale of which should materialize during the course of 2006. This shipyard swung back to profits in 2005 and its production is dedicated to its parent company.

SSN (Stocznia Szczeninska Nowa) moved back into profit in 2005, partly thanks to asset sales, but the outlook looks brighter with an orderbook of nearly 70 ships (45 containerships, 8 ro-ros and 5 chemical tankers) with delivery dates which spread until 2009.

Croatia

At the end of 2005, Croatian shipyards had an orderbook of about 2.2 million gt, about 2.6 million dwt and a total value of about US$2.7 billion) which is, only as far as deadweight is concerned, less than in 2004 (3.2 million dwt) while in all other aspects it is very similar (in 2004 the orderbook consisted of 2.3 million gt with a value of US$ 2.1 billion). This minor change is not due to non competitiveness from Croatian shipyards but due to already full orderbooks and a cautiousness of not booking too remote deliveries while the prices of steel and equipment remain volatile.

The three large Croatian shipyards, Split, Uljanik and 3 Maj have successfully secured orders well into mid 2009 and on some slipways even into 2010. The orderbooks of these yards remain within the tanker and ro-ro/PCTC segments. Trogir shipyard is also booked until the second half 2009 with MR size IMO 2 product chemical tankers.

Shipyard Kraljevica, which is engaged in a series of sophisticated high heat bitumen tankers is the only yard at the end of 2005 that still had an open capacity in 2007 together with Brodosplit BSO, another small shipyard.

In December 2005, Brodosplit successfully delivered the first Stena P-Max in a series of six. This innovative and fully redundant tanker is a good example of Croatian shipbuilders capability to build sophisticated tailor-made products for demanding clients.

Croatia has, in the prevailing high newbuilding market, been able to compete on more standard type tankers such as Aframax and coated Panamax tankers. However, in order to remain competitive in the future, Croatian shipyards are also trying to follow Uljanik's successful diversification into ro-ro and PCTCS where the competition from the Far-East is expected to remain less fierce.

We can expect to see Croatian yards competing for ro-ro passenger ships and ferries. Presently this is restricted to the Brodosplit BSO shipyard which in December 2005 secured a series of four 60 meters and 25 cabins passengers ships for American clients.

The former Victor Lenac shipyard ceased its newbuilding activity and will concentrate on shiprepair and conversions. It expects that its new large floating dock for up to Suezmax size be operational by the end of 2006. Trogir shipyard is also very keen to enter into the shipconversion market more strongly.

Romania

The Romanian orderbook consisted of 630,000 and 1,430,000 gt at the end of 2004 and 2005 respectively. This impressive rise was partly triggered by a series of containerships ordered at Daewoo Mangalia (DMHI), of which 7 units of 4,860 teu are for Niederelbe and 6 units of 5,552 teu are for Hamburg S'd.

Bulgaria

There are two shipyards in Bulgaria: Varna, specialised in the construction of bulk carriers, and Rousse, which is involved in the production of multipurpose vessels.

Turkey

Over the course of the past few years, Turkish shipyards have shown a remarkable dynamism. In 2005, 860,000 gt of new orders were logged onto their orderbooks, which hold 1.25 million gt, against 600,000 gt at the end of 2004. It stood at 310,000 gt at the end of 2003.

That success attracted new investors, who decided to open new shipyards on the Sea of Marmara (Izmit, Ielova), but also on the Black Sea (Samsun) and the Tuzla Bay, where almost all Turkish shipbuilding is concentrated (about 38 yards), causing congestion.

The core of the production consists of ships below 20,000 dwt, principally product tankers (of which 50 were recorded during 2005), containerships (with about 30 orders), general cargo ships and specialised vessels (cement carriers, sulphur carriers').

Russia

The Russian orderbook increased strongly during the course of 2005, reaching 910,000 gt, against 615,000 gt at the end of 2004. It stood at 350,000 gt at the end of 2003.

The Russian builders are taking advantage of the dynamism of Russian ship owners, particularly those specialising in the transportation of crude oil and petroleum products. Significantly, they have an undeniable know-how in shipbuilding, notably in the construction of ice class vessels, and they have attracted Western owners like Stena and Odfjell. They also built subcontracted hulls on behalf of some European shipyards, especially Scandinavian ones.

Apart from the Sevmash shipyard, most of the shipyards are located in the Saint Petersburg region, which benefits from the vivacity of the Baltic economy.

Ukraine

The orderbook of Ukrainian shipbuilders has strongly increased over the course of 2005 to reach 400,000 gt, against 260,000 gt at the end of 2004.

AMERICA

United States

The American shipbuilders still remain very far from the international competitive scene. We can highlight the order at Aker Philadelphia for 10 product tankers of 47,000 dwt for the account of financial investors secured by long term charters to OSG, under the American flag.

The orderbook of American builders was 610,000 gt at the end of 2005, of which nearly 490,000 gt was product tankers.

* * *

OUTLOOK

During 2005, newbuilding prices reached new historical record levels, while the world orderbook, which stood at its highest level, guaranteed the shipyards workloads for an exceptionally long period of time. However, a mis-match between the revenues generated by the ships and corresponding newbuilding prices appeared as of mid 2005 and the sentiment changed. Some analysts started then to mention again the risk of shipbuilding overcapacity, while others predicted that prices would decline in the short term.

In these conditions, what will be the commercial policies of shipbuilders ?

Shipbuilders are first convinced that the need for newbuildings remains very important. As a matter of fact, one has to tackle the growth of maritime transportation, which is linked closely to the increasing requirements of China, India and Brazil, fast growing economies with a strong demographic base. Other expanding sectors, such as gas (LNG, LPG) must also be dealt with. In addition, the implementation of new regulations has triggered a necessary fleet renewal process for certain ship types. On January 1st, 2006, more than 150 single hull VLCC were trading, with the most recent ones delivered in 1996, just about 10 years ago. Apart from a few exceptions, they should all stop trading by 2010. With slightly over a hundred ships in the orderbooks, about 50 additional ships will have to be built before that date in order to ensure merely a renewal of the fleet. As for product tankers, the future impact of the regulation on the transportation of vegetable oils on IMO 2 vessels, to be applied from January 1st, 2007, is still difficult to assess.

Shipbuilders have realised that they are also in a much better position than ever to negotiate with potential customers. The staggering of orderbooks of up to four years in advance is giving shipyards great power, by being able to wait. This privilege once belonged to the owners, who could use it to postpone decision making, while shipyards, in order to maintain the continuity of their activities, had to agree to discounts. Besides, whenever demand weakens for a certain ship type, shipyards can arbitrate, as they have over the past few years, given priority to container ships or LNG newbuildings.

But shipbuilders note also that their newbuilding costs are not going down. Steel prices are indeed no longer going up this year and are likely to decrease in the future. But, there remains a large uncertainty about the price the shipyard is eventually going to pay for the steel plates, whenever a ship's price estimate is to be made, as long as steel plates are ordered by shipyards only a few months before the start of the manufacturing process, i.e. about one and a half years before the ship is delivered. Furthermore, the price of equipment, especially main engines, along with the cost of energy required for the industrial process, keeps on rising. Labour costs also keep on increasing, even if they are being partially offset by better productivity. The growth in production and shipbuilding capacities is generating some tension on the employment market while employers are struggling in order to keep or to attract interesting profiles.

Shipbuilders have had a hard time accurately assessing the cost of a newbuilding with delivery in 3 or 4 years, which has made them increase their margins to cope with uncertainties, including foreign currency exposure.

Finally, most of the shipbuilders have seen weakened financial statements as a result of orders contracted in 2002 and 2003 at very low prices. Even if there is room for improvement in 2006, they still need to consolidate their results.

What is the shipyards' analysis on the current shipbuilding expansion?

As a matter of fact, some fear the consequences that the implementation of new shipbuilding capacities around the world will have, first of all in China, but in South Korea and some developing countries as well, as it could generate an imbalance between supply and demand, and a fall in newbuilding prices in the future.

But in such a fragmented market, it is something of a challenge to be able to think on a global scale and to refrain from investing for the sake of superior interest.

Shipyards' priorities are to benefit from the current boom, to provide satisfying results to their shareholders (major shipyards are listed), to be more competitive than their challengers even if they have to increase their own capacity to achieve this goal, thereby affecting the world's shipbuilding capacity and raising the risk of overcapacity.

Corporations and countries are following their own dynamics. The shipbuilding industry provides numerous employees, subcontractors, suppliers and design offices with jobs, and contributes to the wealth of a whole country. China wants to win market shares and become the world leader by 2015; Japan and Korea will certainly try to keep their current position, which should generate strong competition between them.

However, the prospect of overcapacity is still far ahead and uncertain. So many things can happen in the meantime. Shipyards can still hope that they will be able to adjust their production, similarly to what is being done in other, more concentrated industries (oil, steel, car, electronics). Real estate speculators could well manage to take control of particularly well located sites and some consolidation activity could take place.

Will shipowners keep on ordering newbuildings or, on the contrary, will they postpone their investments?

Shipowners have enjoyed the shipping boom, the rise in freight rates, as well as strong profits on ships sales, even more than shipyards. Never have they found themselves in such a good position for making investments. Before the boom, they used to operate in a low-margin environment and therefore can still think of current freight rates as being high, with market conditions favourable for launching newbuilding programs. History tends to show that shipowners are reluctant to invest when the market is low because of a lack of visibility or simply because they don't want to spend all their cash. Contrarily, there have never been so many ships ordered than during the past three years, despite prices being at their highest level.

However, the mismatch between freight rates and ship prices is now being felt and many shipowners are now awaiting an adjustment in newbuilding prices in order to take a position.

Some of them can also hesitate to order newbuildings with delivery dates as remote as 2009 or 2010. But others realize that they have been postponing their investments for too long, hoping for the market to go down, only to see they may have to wait for several years to take delivery of the ships they need for their fleet renewal operations. This could well be an encouragement to take a different perspective on the market and make new decisions.

VOLUMES AND PRICES

The volumes ordered in 2003 (110 million dwt), 2004 (115 million dwt) and 2005 (95 million dwt) have saturated the shipyard's capacities and stretched their horizon to first 2-3 and then 3-4 years. It is likely that neither shipowners nor shipbuilders want to go any further, and in 2006, new orders may well equal the world's yearly output, now set at about 75 million dwt.

The impact of the new IACS Common Structural Rules, which are to enter into force on April 1st, 2006 remains difficult to asses. Will there be a rush for new orders before the deadline?

Prices of many ships reached new historical records in 2005, but these increases should now be behind us, except for a weakness of the dollar. The situation that prevailed in the newbuilding market during the past three years owes much to the bullish developments in the three main freight markets (dry bulk, tanker and container). Should freight and charter rates decrease further, along with shortening charter periods, it is then likely that the second hand market may provide better opportunities and may push newbuilding prices down. During the past few years, newbuilding prices have also been pushed up by the many resales at prices higher than contract prices from shipyards. The drop in freight rates is now having considerable influence on resale prices. For example, the price for a Handymax bulker for prompt resale has gone down from $ 40-42 million to $ 28'29 million in six months, less than its estimated newbuilding price of $ 30.5 million for a delivery in 2008/2009. We could be entering a moderately bearish market where time plays for buyers, and where it's worth waiting. However, this bearish trend may also encourage buyers to take action, all the more than most shipowners have accumulated considerable gains over the last years.

Marketing strategies will probably vary from one shipyard to another, based on their individual situation, assessment of the market evolution and possible arbitrages and there'fore, we could expect price spreads between various shipbuilders. While some Chinese shipyards were ready to sell a VLCC for $ 105 million at the beginning of 2006, Korean or Japanese yards were still asking $125 million for the same ship type.

2006 might turn out to be a year of healthy soft landings for the new-building market.

Shipping and Shipbuilding Markets in 2005

I N D E X